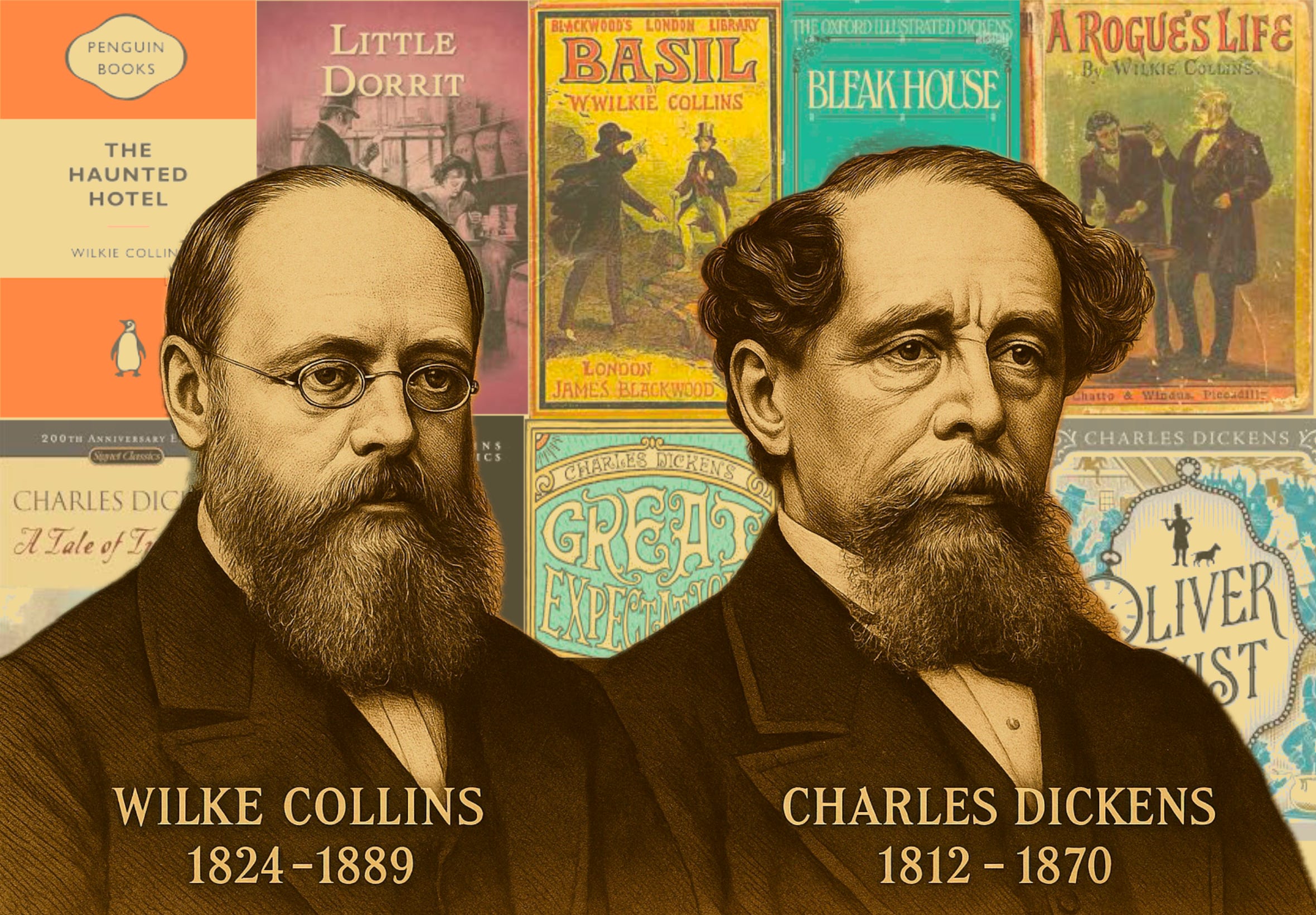

The Brotherhood of Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens

The creative genius of two masterminds combining

There’s something electric about a good partnership. I have it with my crime partner Edward Anderson. Two creative minds crash into each other and something bigger than them comes out of the wreckage. It’s rare. But when it happens, you get revolutions, not just stories. Think Lennon and McCartney, Hitchcock and Herrmann, and Dickens and Collins in Victorian literature.

Most people know Dickens, the factory kid turned social critic, but fewer know the man who helped him reshape the crime genre from the inside out. Wilkie Collins wasn’t Dickens’s sidekick. He was a force. And when their paths crossed, they created a storm that still echoes in detective fiction, psychological thrillers, and courtroom dramas today. Their friendship was messy, creative, and at times deeply co-dependent.

The Addicted Genius Who Reinvented Crime Fiction

Wilkie Collins (1824 to 1889) was no background character. Born into an artistic family, his father was the painter, William Collins, Collins grew up in London surrounded by canvases. He started out studying law, but it never stuck. What did stick was his obsession with writing, and more than that, exposing the rot beneath Victorian respectability.

By the 1850s, Collins had started a career that would take him straight into stardom. His 1859 novel The Woman in White was a bestseller. It was the Gone Girl of its time, mixing suspense, social criticism, and a good old-fashioned gothic mystery. Then came The Moonstone in 1868, widely credited as the first full-length detective novel in English.

But Collins wasn’t just about crime. He used his stories to skewer the Victorian legal system, marriage laws, and how society treated women. He lived outside those norms too, refusing to marry, keeping two relationships running at once, and raising children out of wedlock. The man lived his truth, and his truth didn’t care what the Church of England had to say.

In his books, he portrayed women as strong, courageous, and having their own identity. They were bold characters who pushed the boundaries of social acceptance.

Collins was hooked on laudanum, a legal opium tincture, by the end of his life he was in constant pain from gout and half dependent on the stuff to function. Writing caused him great pain but it was something he couldn’t stop. He left behind more than thirty novels, along with a string of plays.

The Mastermind With a Megaphone

Charles Dickens (1812 to 1870) was twelve years older than Collins and already a literary juggernaut when they met. Born in Portsmouth and battered by poverty after his father was thrown into debtor’s prison, Dickens worked in a boot-blacking factory as a child, an experience that never left him. His anger toward institutional cruelty burned through every novel he wrote.

When The Pickwick Papers hit in 1836, he became a household name. He pumped out classic after classic: Oliver Twist, Bleak House, David Copperfield, A Christmas Carol, and Great Expectations, all while maintaining a public image as the moral compass of Victorian England. He was complex, driven, controlling, and more than a bit obsessed with his image.

Dickens loved theatre, though he wasn’t a fan of visual art. He acted, performed readings to massive crowds, and threw himself into dramatic roles like he was born on stage. That’s how he met Ellen Ternan in 1857, an actress who would become his mistress and cause a massive rift in his marriage. The unconventional relationship was something he had in common with Collins.

He stayed in Folkestone often, maybe to escape the chaos. Despite all the scandals and contradictions, Dickens used his fame to push for real change, tackling issues such as child labour, poorhouses, and corrupt law courts.

A Creative Brotherhood

Dickens and Collins met in 1851 through their mutual obsession with amateur theatre. Dickens saw something in Collins, maybe a protégé, a partner, or a kindred soul not afraid to live outside the norm. Their friendship took off fast. They travelled together, wrote together, and even shared the stage. Collins became a regular contributor to Dickens’s periodicals Household Words and All the Year Round, and their collaboration blurred the line between editor and equal.

It’s possible that Dickens based the character of Richard Carstone in Bleak House on Collins, a young man tossed from institution to institution for work, unsure of where he belongs.

When Collins’s brother married Dickens’s daughter, it caused a rift. Collins’s brother was irresponsible with money and, despite a reasonable allowance from Dickens, found it hard to live within his means. Dickens’s criticism of this caused Collins to defend his brother, which was the beginning of the two writers drifting apart.

When Dickens died in 1870, Collins was left without his closest collaborator. He kept writing, but there was a shift. He never really recovered from Dickens's death.

Not Just Dickens’s Shadow

People like to frame Collins as Dickens’s sidekick. That’s wrong. Collins wasn’t in anyone’s shadow. They pushed each other to be better, and sometimes worse. But their friendship gave Victorian literature its edge. It birthed sensation fiction. It gave working-class readers stories with teeth. It gave us detectives, secrets, and broken men hiding behind polite society’s masks.

They were a complicated, creative, co-dependent mess, and they changed the game. If I could have one literary wish, it would be that Collins had finished Edwin Drood, because I believe he knew the great man well enough to have completed the story in a way that truly satisfied.

The books which help you most are those which make you think the most. The hardest way of learning is by easy reading; but a great book that comes from a great thinker is a ship of thought, deep freighted with truth and beauty. — Wilkie Collins

Great read!

I enjoyed this. An interesting read about an important part of literary history.